- Home

- Howard Anderson

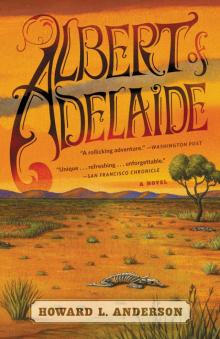

Albert of Adelaide

Albert of Adelaide Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Reading Group Guide

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

It seems fitting to dedicate this book to an Australian soldier I met at a bar many years ago in Sydney. All I can remember about him was that he had a bad bayonet scar from service in Malaya and that he got me hopelessly lost on the New South Wales rail system before he passed out.

Preface

The county that stretches from Melbourne in the south to Sydney seven hundred and fifty miles up the coast is green with trees and paddocks. On the farms along the coast, sheep graze in the fields, and foxes eat the rabbits that in their turn eat the lettuce growing in the gardens. The sheep, the foxes, and the rabbits live their lives no differently than did their ancestors in England not so many generations ago.

The animals and men that used to live along the coast, in the days before the bush became suburbs, don’t come to this part of Australia much anymore. Kangaroos and wallabies have found ways to prosper, but the rest have been pushed back into the deserts or survive in zoos as relics of the past. Tasmanian devils snuffle along the concrete floors of their pens next to panda bears from China. Cassowaries feed in fenced enclosures next to kudus from Africa.

The original inhabitants of Australia have become curiosities to be stared at, along with other unwilling creatures from continents far away. Times have changed along the coast, and there is no room for those that used to live there. The animals living in the zoos remember that Australia once belonged to them.

They talk of a place far away in the desert where things haven’t changed and the old life remains as it once was. As with most stories, hope rather than truth wins out with each telling, and in the end the only way to be sure of what’s real and what’s not real is to go to the source of the tale.

1

Desert Crossing

The tracks of an old railway line run from Adelaide in South Australia to Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. For many years, as each train passed by on its thousand-mile journey between the two towns, passengers threw their empty beer bottles from the windows of the cars into a landscape that seemed unimportant to them. The broken bottles accumulated along the roadbed and the route from Adelaide to Alice Springs became a shining ribbon of broken glass.

At Alice Springs the railway line continues, south to north, in an almost undeviating straight line across the center of the country, and passes through the towns of Tennant Creek and Katherine. The tracks parallel a road that was widened many years ago to take war materials from Alice Springs, in the center of the country, to Darwin on the northern coast. The war drifted away from Darwin to its conclusion in other parts of the Pacific, and traffic along the road slowed to almost nothing. It took almost another lifetime to complete the final nine hundred miles of track from Alice Springs to the coast. North of Alice Springs the railway line disappears into a series of mountain ranges that cross the center of the continent.

Beyond the mountains is a red desert. It is a desert of vast distances and, when closely examined, of great variety. The occasional cliffs and gorges are red in color, as are the soil and sand that cover sections of the desert floor. The color fits well with the blue and normally cloudless sky that on occasion brings water to the dry riverbeds that cut across the land.

The desert is covered in patches of short, stunted grasses that have won a marginal hold in the red, sandy soil. Scattered across the sand and grass, desert grevillea bushes seem like giants in the treeless flats. In some places the bushes grow close to one another, and small birds flutter among the branches. The birds don’t sing, and the silence of the desert is broken only briefly by the flutter of their wings.

There are paths in the desert where passing animals have walked the weak grasses into extinction. These tracks, unlike the railroad, follow no set direction. They wander aimlessly through the flats and up and down the banks of the dry rivers, heading to destinations unknown. The age of the tracks is impossible to tell, for the grass grows back slowly in those parts of Australia.

In the early morning of a day long after the war, a small figure walked slowly along one of the winding tracks somewhere to the east of Tennant Creek. On close examination, the figure didn’t look any different from most of his kind. He was about two feet tall and covered with short brown fur. He had a short, thick tail that dragged the ground when he walked upright and a ducklike bill where any other animal would have a nose.

The only thing that set Albert apart from any other platypus was that he was carrying an empty soft drink bottle. It was his possession of a bottle, coupled with the fact that he was hundreds of miles north of any running water, that made him different.

Albert had crept away from the railway station at Tennant Creek and into the desert three nights before. For the first day after leaving the station, he had walked along the railroad track. A train had come by late in the afternoon and Albert had hidden himself in a bush near the roadbed. No one had seen him, but he was almost hit by a half-full bottle of Melbourne Bitter thrown from a second-class coach. After that, Albert stayed away from the tracks. From a distance, he had paralleled the roadbed north for the last two days, because without that landmark Albert would have been hopelessly lost. As it was, he was just confused.

The problem was that Albert had no idea where he was going, or exactly what he was looking for. The stories had been vague at best… somewhere in the desert… a place where old Australia still existed… keep going north… the Promised Land. Those descriptions had sounded good in Adelaide, but they were worthless in a desert where every direction looked the same.

His escape from Adelaide and the trip to Tennant Creek had been easier than he expected. Security on the smaller animals was minimal. It had been only a matter of time before a careless attendant left his enclosure latch unfastened. Then a quick midnight run through the deserted park and a short swim across the River Torrens had gotten him into the city proper.

Some of the larger animals had been brought to Adelaide by train and then to the zoo by lorry. They told him about the trains and described how to reach the railroad yards. Traffic on the city streets was infrequent late at night, and Albert managed to get across town to the station by hiding behind rubbish bins from the occasional passing automobile. After that, he had hopped a freight to Alice Springs and then another to Tennant Creek, the entire trip courtesy of the South Australia railway.

With the limited resources available to him, Albert had tried to prepare for the journey. He had saved part of his meal at each feeding and put the grubs into a discarded popcorn box he had pulled into his cage when no one was looking. Water he had taken from his dish and put in the stolen soft drink bottle. His planning had gotten him to Alice Springs and then to the desert outside Tennant Creek. Now, he was out of food, out of water, and out of plans.

He had filled his bottle the night he left the train at Tennant Creek, but his bottle didn’t hold that much. The water had run out yesterday and Albert knew that if he didn’t find more that day, he would die. A platypus is an animal that lives in or near water all its life and can’t survive without it. He didn’t mind the dying as much as he minded not living long enough to find the place he was looking for, somewhere without people and without zoos.

As the day grew longer, Albert began to hallucinate. Dreams of water would mix with the heat waves rising in the air, and Albert could see the Murray River. He could feel himself slide down the mud ramp in front of his burrow and into the coolness of the river. He would float down the river and watch the green banks pass by. Just when he was sure that he was back for good in the place where he was born, the river would evaporate, and he could see faces smeared with cotton candy and jaws that dribbled popcorn. The faces laughed and handless fingers poked at him through wire mesh. The horror of the visions caused Albert to start shaking, and when he did the faces disappeared. In their place, the emptiness of the desert and the heat of the day would push their way into Albert’s consciousness, and he would force himself to begin walking again.

As the day wore on, the brush became thicker and the desert began to give way to bush. Most of the brush was taller than Albert, and he lost sight of the horizon and the railroad track. As the sun changed position in the sky, it became more difficult to tell exactly in which direction he was walking.

After one of the series of hallucinations passed, Albert noticed something in a clump of saltbush a few yards from where he was walking, something with a rectangular outline deep in the thicket of brush. Ignoring the pain from being scratched by the branches, Albert pushed his way into the brush until he came upon a weathered sign that read:

PROPERTY OF THE SOUTH AUSTRALIA

RAILWAY

TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED

The Management

Just then the wind came up, and Albert knew that it wasn’t going to be his day.

He struggled out of the saltbush and once again began walking in the direction he thought was north. The wind blew harder and dust began to swirl around him. Albert shouldered his way through the dust for some distance. He ran into clumps of brush several times and instinct alone told him which direction to take. The dust in the air became thicker, and the world disappeared in a reddish-brown haze. It wasn’t long before Albert lost his way completely.

When he realized he might not be going north any longer, he gave up. He was afraid that he might have turned back south, and he didn’t want to die any closer to Adelaide than he had to. Albert saw a large desert grevillea through the dust and pushed his way through the wind until he reached it. He crawled under the bush and lay down. The bush blocked a little of the wind and it seemed calmer there. Albert closed his eyes and held his soft drink bottle against his chest. He began laughing because he knew the South Australia railway would never get the chance to prosecute him.

As Albert lay under the bush, red dirt and sand began to drift over him. He began to dream that the sand was the water of the Murray and that he was going home. Above him the wind rattled the branches of the bush.

As the branches rattled, the bush began to sing. The song was very faint. Albert heard “glory,” followed by “banks” and then “reedy lagoon.” It was a song that Albert had never heard before, and he couldn’t understand why a bush would want to sing it to him.

Albert didn’t like the song. It took him away from the banks of the river and brought him back to the desert. He wriggled in closer to the roots of the bush and tried to think of home, but the song wouldn’t leave him alone.

“I once heard him say he’d wrestled the Famous Muldoon.”

Why would a bush listen to anyone? Who was Muldoon and why was he famous? Albert lay there asking himself those questions. The bush couldn’t sing very well. It was off-key, and that bothered Albert. It’s hard to lie down and die when you are upset. Albert slowly rolled out from under the bush and stood up in the wind. He cocked his head and listened.

And where is the lady I often caressed,

The one with the sad dreamy eyes.

She pillows her head on another man’s breast.

He tells her the very same lies.

The song was scattered through the surrounding bushes by the wind. The wind would shift, and with each shift the singing could be heard coming from a different place.

Albert looked out into the dust storm that obscured the desert. He couldn’t see more than a few feet, so there was hardly any chance of finding the singer. Yet it was a chance, and one that hadn’t been there before. Albert put the bottle under one arm and started walking straight into the wind.

The sand in the air bit into his face and forced him to keep his eyes closed. He pushed on, walking into as many bushes as he walked around. The song flowed out of the wind and washed over Albert like the waters of the river that wasn’t there.

High up in the air I can hear the refrain

of the Butcher bird piping his tune.

For spring in her glory has come back again,

to the banks of the reedy lagoon.

With each step the song grew louder. He tried to walk faster. He was sure that around the next bush, or the one after that, he would find where the song was coming from. Just one more verse was all he needed to hear, but the last verse never came.

Albert stopped in front of a large saltbush. He stood for a long time, but all he could hear was the wind and the rustling of the branches. The feeling of hope and his last link with the Murray River collapsed, and all that remained was the certainty that this was where it would end.

All at once Albert smelled smoke and heard a gruff voice say, “If this is spring in her glory, I can bloody well do without it.”

Albert jumped at the sound of the voice. If he hadn’t been so tired, he would have run toward it. As it was, he had only enough energy to walk around the saltbush.

There, in the middle of a clearing, with the wind scattering sparks and ashes in all directions, was a small fire. A metal tripod had been placed over the fire, and hanging from the tripod was a battered billycan. Steam was escaping from under the edge of a small plate that covered the top of the can.

On the far side of the clearing, partially obscured by the dust and the flying ashes, a blanket lay spread under a bloodwood tree. The blanket fluttered in the wind and the only thing that kept it from blowing away was the heavy pack resting on it.

Standing over the blanket, with his back toward Albert, was a bulky figure wearing a long drover’s coat and a gray slouch hat, trying to tie a dirty piece of canvas between the tree and a saltbush a few feet away. Each time the creature came close to getting the rope tied, the wind blew the canvas hard enough to pull the rope from his grasp. With each failed attempt, the creature would mutter, “Spring, bah!” and redouble his efforts to tie the canvas to the bush.

After many attempts, he managed to get the canvas tied off so that it formed a barrier against the wind.

The figure in the long coat waited until he was sure the knots would hold the canvas, then nodded in satisfaction and turned back toward the fire. This gave Albert a clear view of him: a large wombat with a graying handlebar mustache.

The wombat, intent on keeping the wind from blowing the hat off his head, didn’t notice Albert watching him from the far side of the clearing.

When the wombat reached the fire he turned his back to the wind, which had shifted and was now coming from Albert’s direction. The wombat crouched down and fed small pieces of brush into the fire under the can. As he did, he began to sing in a whooping monotone that carried over the wind.

My bed she would hardly be willing to share

were I camped by the light of the moon…

The wombat stopped singing in midverse and began to laugh.

“Ain’t that the bloody truth… not to mention if I got upwind… It’s not the keeping square tha

t has kept me single… It must be something else… I wonder what else it could be… I can lie pretty well… that can’t be it… I know it’s bathing… true love demands soap and water… a habit I don’t intend to cultivate.”

The wombat laughed again and began whistling the song as badly as he’d sung it.

If he hadn’t been certain that there was water in the can hanging over the fire, Albert would have crept back into the bush and let someone more desperate than himself confront a singing wombat in a drover’s coat.

Instead, he took a deep breath and started to say “Excuse me” in a loud voice. What came out was a garbled hiss. Albert hadn’t spoken a word to anyone since his journey began, and he hadn’t realized how dry his throat was. The wind had quieted briefly as he tried to talk, so the hissing noise carried clearly to the whistling wombat.

The wombat jumped several feet in the air and at the top of his lungs screamed, “Snake!” Upon landing, he grabbed a heavy stick that was lying by the fire and began beating the ground all around the spot where he had been crouching. After he finished pummeling every inch of ground within reach of his stick and knocking his firewood all over the clearing, the wombat stopped, looked around, and saw Albert for the first time.

He stared at Albert a few moments, then began to walk toward him. Albert grabbed his soft drink bottle by the neck and prepared to sell his life dearly. Just then the wind rattled a saltbush next to the canvas windbreak. The wombat turned and ran toward the offending bush and at the same time shouted in Albert’s direction:

“Thank God, reinforcements. Hurry up and bring your bottle. There’s a snake around here, but I’ve got him on the run.”

Albert of Adelaide

Albert of Adelaide